Life Otherwise

On July 16, 2025, NASA discovered a mysterious planet sending signals from 154 light-years away, which it affectionately referred to as the “Super Earth.” Meanwhile, America has witnessed its first human-caused extinction of species: the Xerces Blue Butterfly. I saw somewhere that a new filter can now turn exhaust gas into oxygen. On the same day, I read about the deadly pollution in Memphis caused by Musk’s xAI Data Center.

Once again, the human species has reached a critical stage of survival filled with dilemma and duality. As hope and hopelessness spiral, we are left to ask: where is Earth headed? And what will our future be?

Powered by Berggruen Institute’s Future Humans Project, Proxima Kósmos explores the intersection of science, technology, art, design, and science fiction and radically imagines an alternative solar system using existing scientific theories, models, and speculations. The result is nine alternative versions of Earth — nine possibilities of what our world could have been.

“Imagine a planet not unlike our own, warmed by an orange sun,” states the project’s introductory essay. “For over a year, world-class scientists have rigorously simulated alien life forms. Life that is strange, yet familiar. Our cousins, evolving just beyond the horizon of spacetime.”

After the opening slides, the visitors see the deep space unfold in front of their eyes, landing on Phaínōterra, the Phosphine Earth, developed by Dr. Sara Seager, Professor of Planetary Science and Physics at MIT, and Dr. Iaroslav Iakubivskyi, a postdoctoral fellow at the Department of Earth, Atmospheric & Planetary Sciences at MIT.

Phaínōterra is modeled after Earth’s neighbor, Venus, whose atmosphere contains phosphate gas. Phosphine, a highly reactive element, does not persist naturally. Therefore, the discovery of phosphate gas and amino acids in the planet’s atmosphere serves as convincing testimony that there might be alien life present on our neighboring planet.

Lab studies have shown that while carbon-based lifeforms, as found on Earth, cannot survive in such an environment, sulfur-based lifeforms are a possibility. On Phaínōterra, the visitor can zoom into the cloudscape (atmosphere) or the waterscape (sulfuric acid ponds) to view the biomolecules that can survive these highly acidic environments: alien life at the very beginning of evolution.

But Proxima Kósmos is not another fancy digital visualization of wild imagination. It is the combination of breathtaking art and meticulous scientific speculation.

Every planet and its corresponding life form is supported by rigorous scientific research, making them plausible. In simpler terms, these alien lives could have been reality in a parallel timeline because their existence, or at least the fundamental components that support the probability of their existence, have been successfully simulated.

Not in a lab, either, but using extreme environments already existing on Earth.

For example, Phaínōterra’s sulfuric microorganisms are created using a sulfuric lake in Indonesia, atop an active volcano. It’s not as if the investigators are saying alien life could exist merely because there is no reason why it cannot. Rather, they’re supporting their statement by proving that some molecules already exist in a similar environment right here on our home planet.

That forces not only the researchers, but every individual, to completely reconstruct our understanding of what life is and could be and, eventually, what planets can become.

Magikos, the Magic Earth, is the perfect example of that radical reconstruction.

Led by Dr. Sara Walker, Professor at the School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University, Magikos is a planet that reproduces. Its offspring, the Baby Magikos, shine timidly next to the mother planet, young but eager to evolve.

This might sound outrageous at first glance: how can a planet give birth to another planet?

Yet, the fundamentals supporting the possibility of planet reproduction like that of Magikos, again, already lie on Earth.

The Assembly Theory, a new theoretical framework developed by Dr. Leroy “Lee” Cronin, Regius Chair of Chemistry at the University of Glasgow, and Dr. Walker, helps researchers detect systems capable of generating complexity at large scales — systems with the potential to form biological systems.

Magikos is the result of adapting the Assembly Theory on a planetary scale, transitioning from a biosphere, where biology exists, to a technosphere, where the planet and its civilizations — biology and technology — coexist symbiotically. At this point, the planet itself can be considered alive and capable of reproduction.

As a work in progress, there are only three fully developed planets in Proxima Kósmos, each with specific scientific findings, hypotheses, timelines, simulations, and even essays and fictions available for further exploration. However, the remaining planets ask questions that are equally critical to human’s understanding of life.

For example, Nousterra reverses the hierarchy of biology and focuses on inorganic evolution. More specifically, the possibility of light/photons as the basic building blocks of life. Akroterra is earth with neverending Ice Age, where silicon-based microbial life exists in subterranean caves and lava tubes

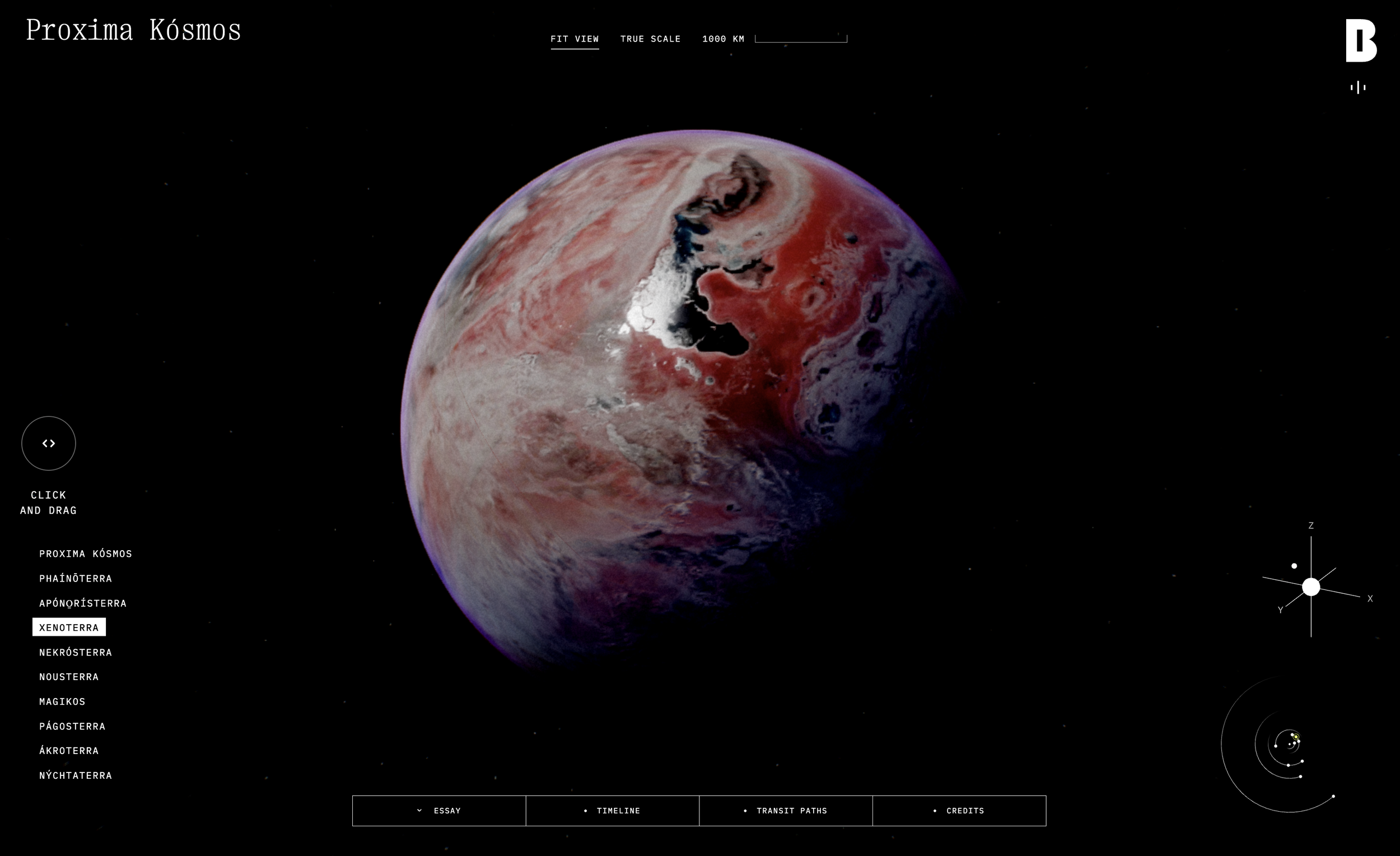

The co-orbitals of Apónōrísterra, Nekrósterra, and Xenoterra are versions of what earth could be or once was. Nekrósterra, or Death Earth, is a morbid warning of a lifeless Earth. Apónōrísterra goes back in time, and recreates Earth in its earlier stages of development. Xenoterra, the Strange Earth, is populated with robots that currently roam the Northwestern University campus.

“Each modular unit has its own brain, metabolism, and muscle. They aren’t like us—obligate multicellular organisms. They're more like modular marine invertebrates—independent, but cooperating,“ said Dr. Sam Kriegman, Principal Investigator of the tri-orbitals, Assistant Professor of Computer Science, Mechanical Engineering, and Chemical and Biological Engineering at Northwestern University.

A few hours before I began working on this review, I found out about UK-backed space mission aimed at “detecting and mapping phosphine, ammonia, and other hydrogen-rich gases that are not expected to occur naturally on Venus” to validate if alien life exists on Venus — “balloon mission,” as anticipated by Phaínōterra’s investigators.

Sitting on the intersection of science, literature, art, and technology allowing the most radical imaginations to materialize, Proxima Kósmos encourages its viewers to reframe how they think about life on Earth and our impact on the planet and the universe. Instead of seeking a solution within an existing structure, the viewers are encouraged to build a new world beyond current configurations: to embrace life otherwise.

Let’s build alien worlds.

Written by Xiao daCunha

Images: proxima-kosmos.com